How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database

Mariam Ghani & Chitra Ganesh

2004

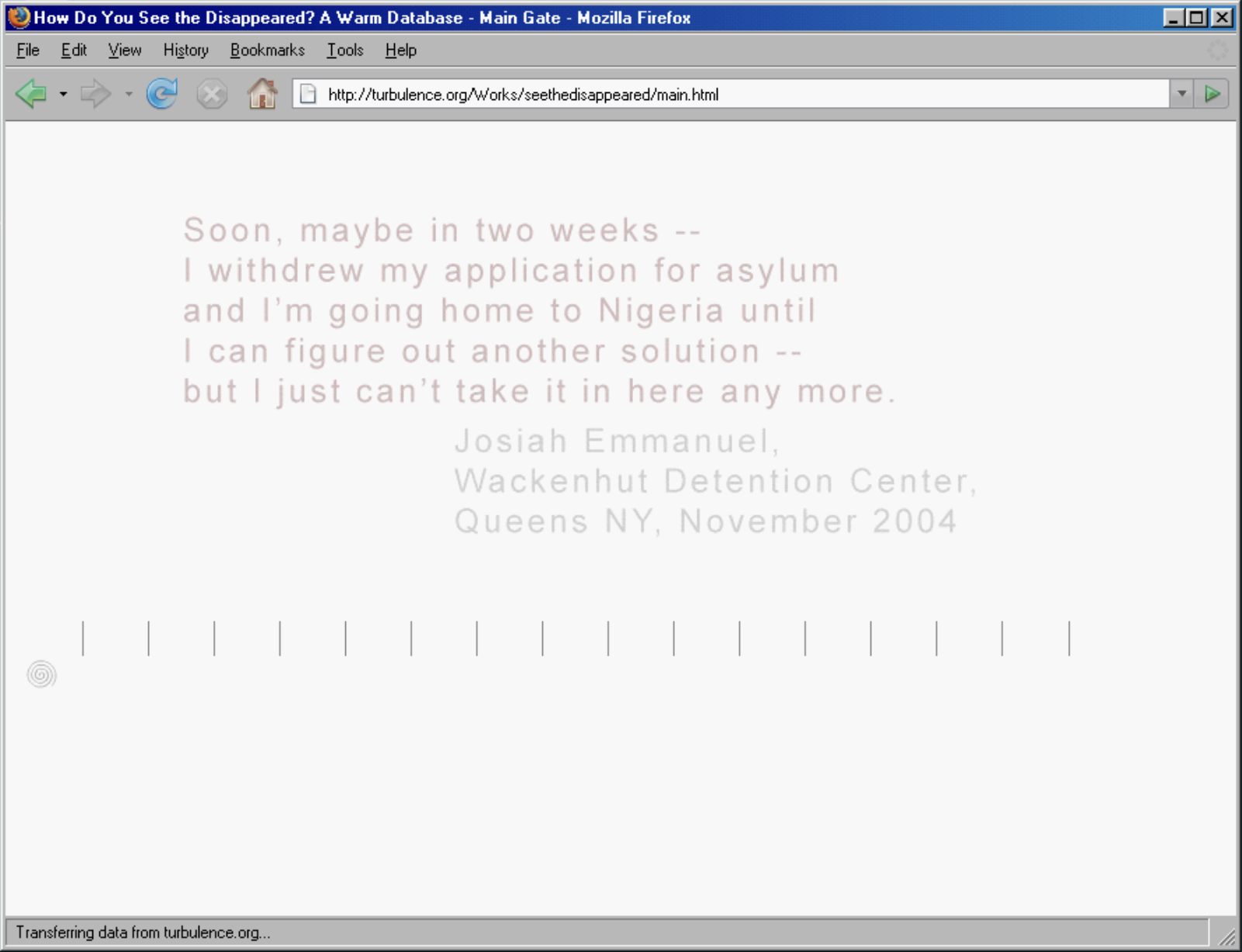

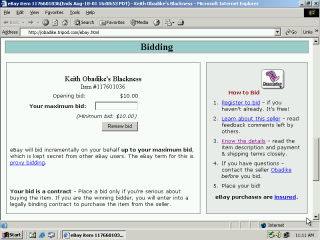

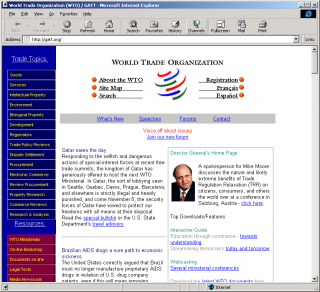

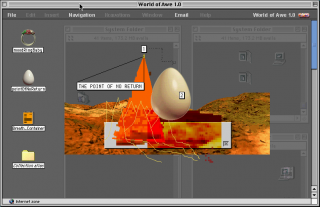

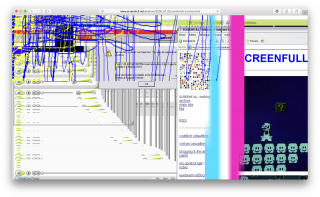

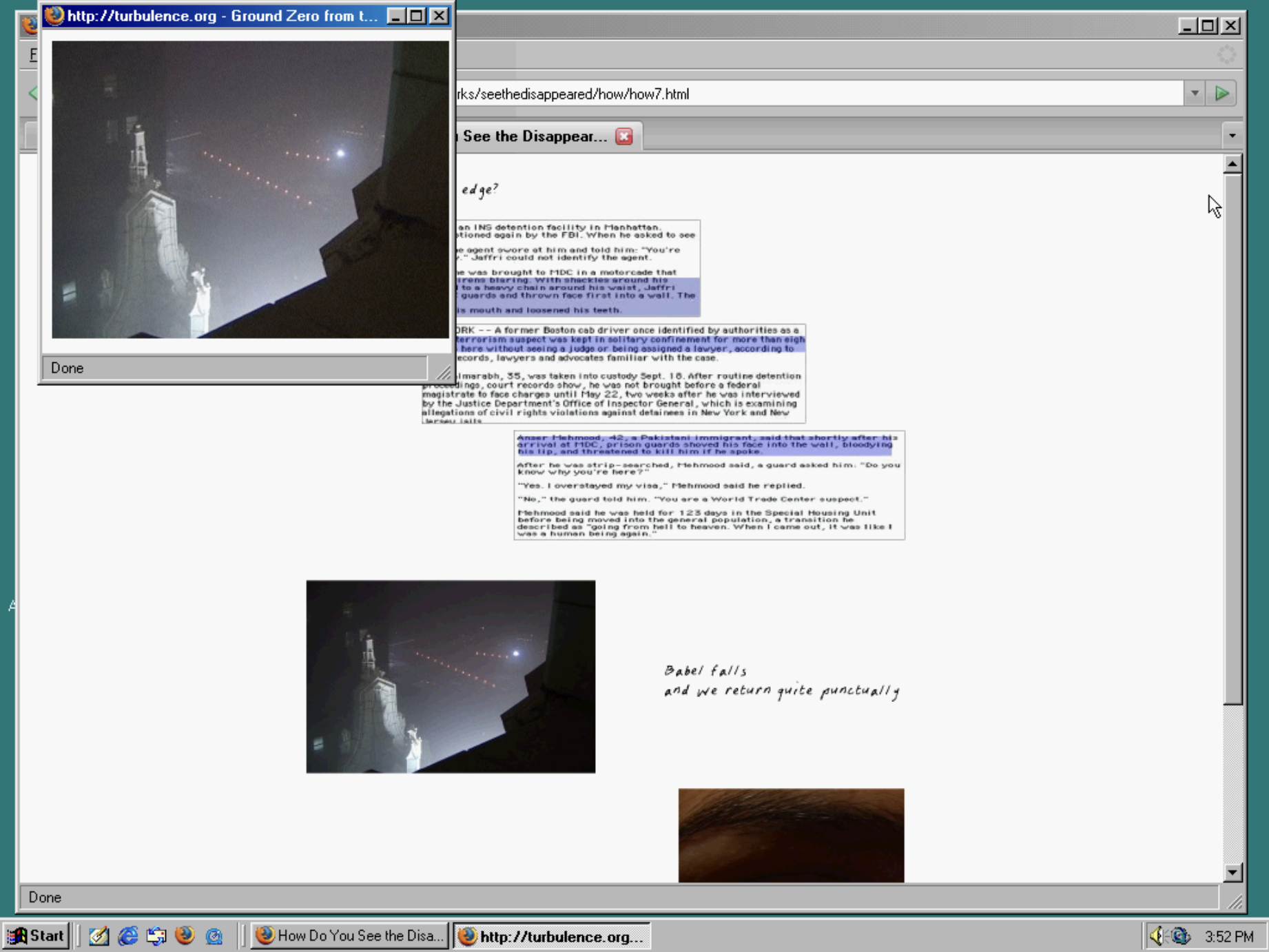

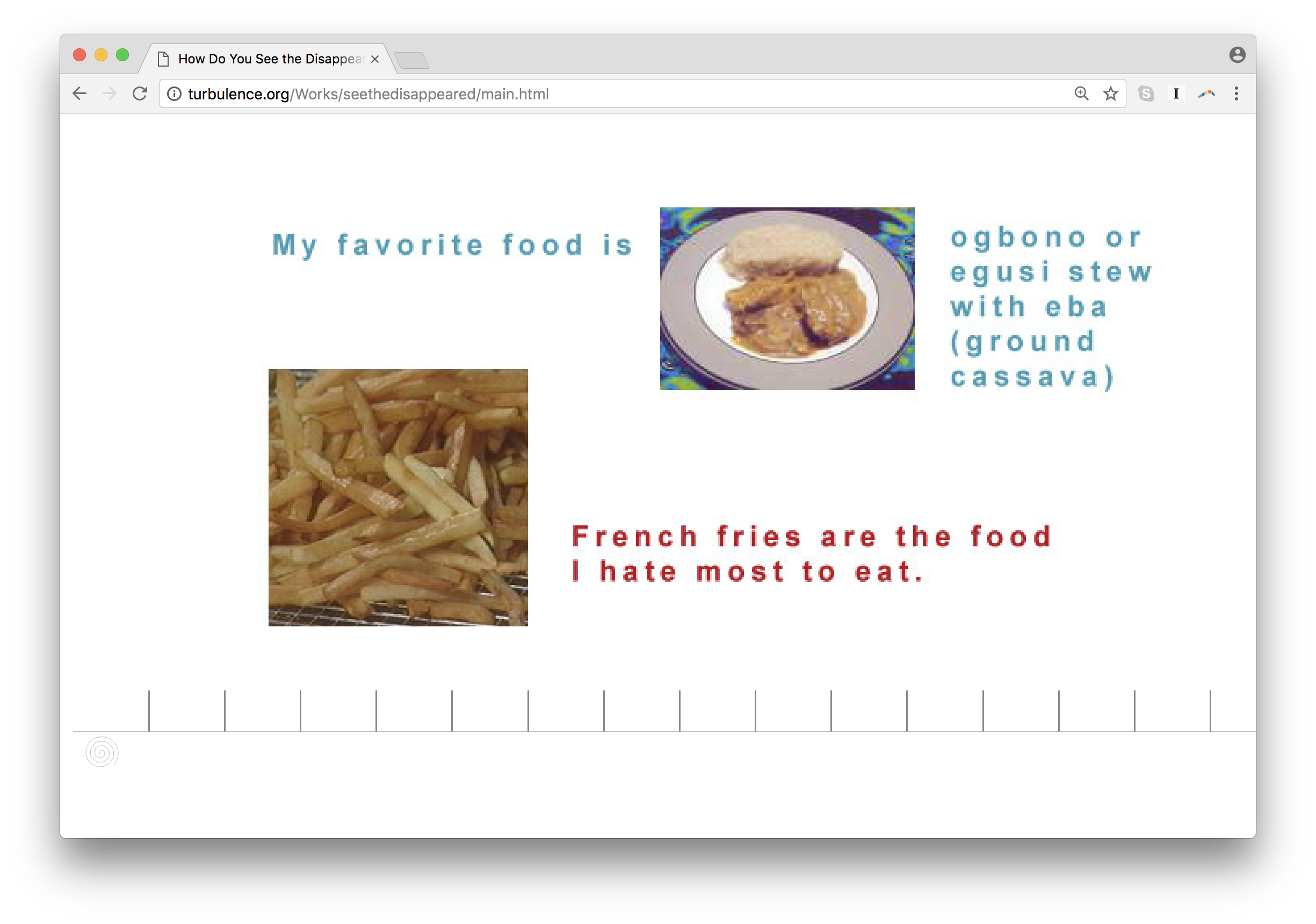

How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004), commissioned by the digital art organization Turbulence, responded to data-gathering and surveillance in the wake of 9/11, and its role in rendition, deportation, detention, and other forms of political disappearance. In opposition to state-sponsored processes of surveillance and erasure, the project proposed a concept of “warm data”–deeply personal but non-identifying information that spoke to the lived experience of being subjected to political invisibility of various kinds.

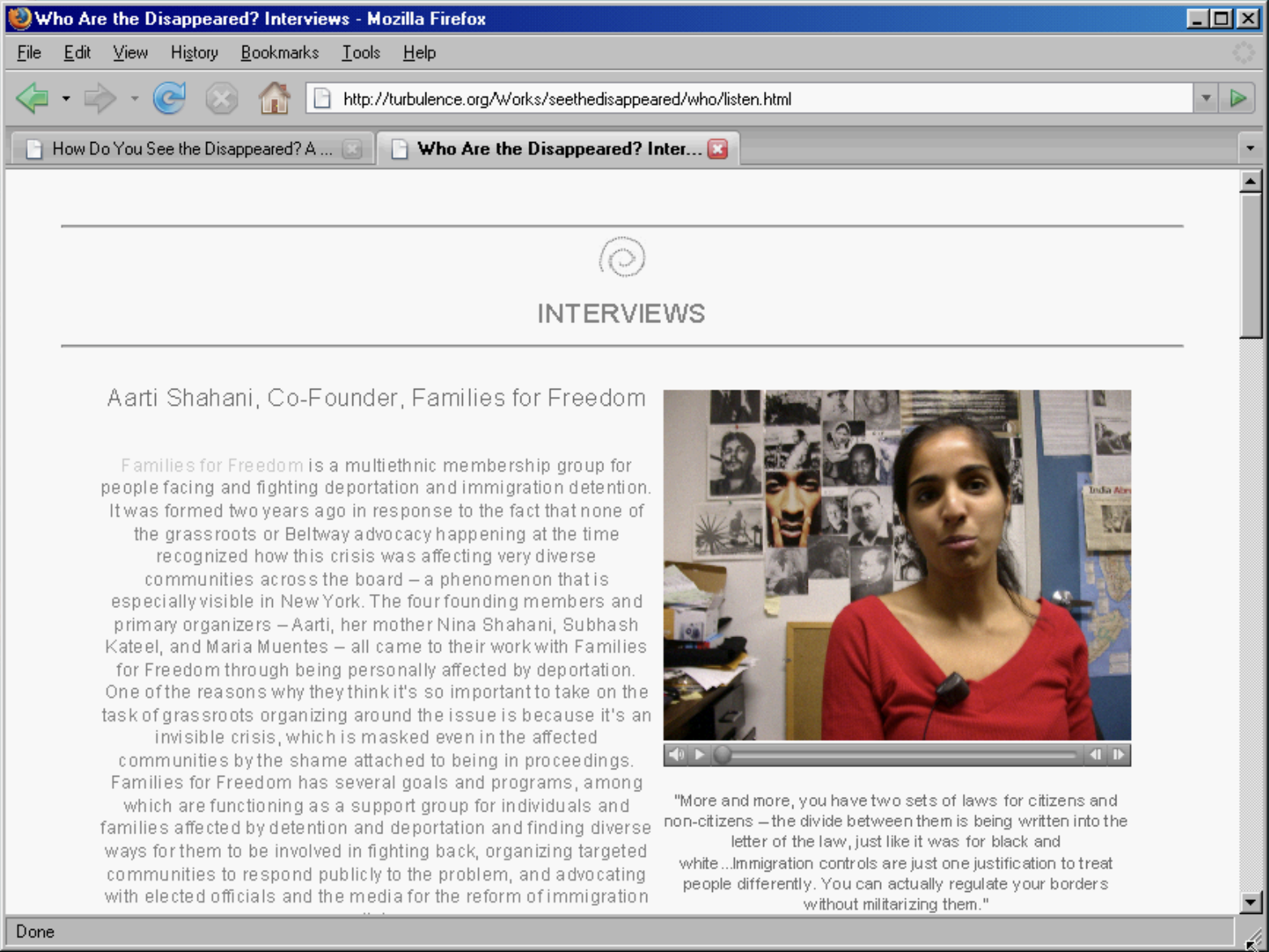

The web-based project featured a hypertext essay, watercolor portraits of the Disappeared, a questionnaire, and visualizations of the answers, as well as accounts of activist efforts and links to political resources. Through warmth and subtlety, it sought to destabilize the cold, calculating logic of the archive, while including concrete calls to action on behalf of vulnerable communities.

This project, which was made with Rob Durbin and Ed Potter, marked the beginning of a larger, ongoing collaboration between Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani titled Index of the Disappeared, an archive of “renditions, redactions, detentions, and deportations.” Through this long-running effort, Ganesh and Ghani have explored the logic and limits of the archive, and its potential as a site for social change.

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

VISIT WORK

(Presented in emulation with Flash and QuickTime plugins.)

“That’s the thing that really became apparent around this time: your databody was incredibly vulnerable. Things that happen to your databody actually could affect your real body.”

– Mariam Ghani

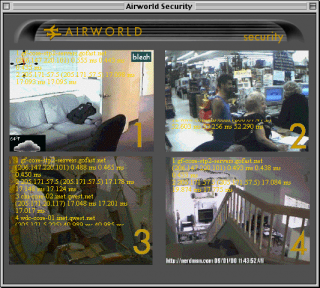

In the years following 9/11, the US government adopted data-driven surveillance techniques that particularly targeted immigrant groups.

Read an interview with Ghani and Ganesh

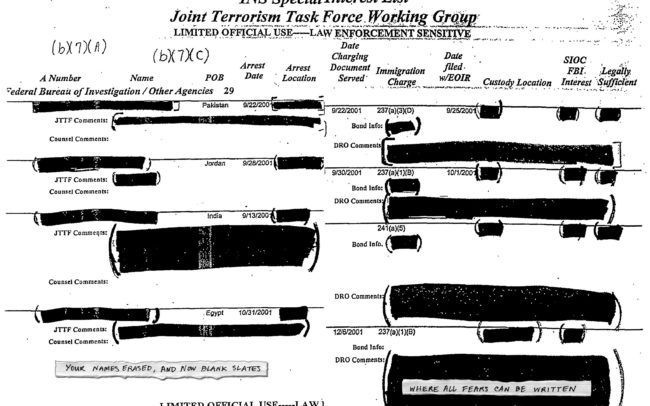

“Thousands of Arab and South Asian Muslim men were questioned by the FBI and local law enforcement about their connections to the tragic events, often on the flimiest of premises,” Ghani writes. “Soon after, an alarming series of midnight raids and surprise sweeps by the INS in those same neighborhoods led to the detention of more than 700 men, initially picked up and placed in custody on standard immigration violations, who became known as the ‘special interest’ detainees.”

The “special interest” detainees were held, without charge, and without even the release of their names. “Meanwhile, the Department of Justice had released one piece of information about the detainees: a list of their nationalities,” Ghani recounts. “The general publc thus knew one thing about these men, and one thing only: they were Arab, they were Pakistani, they were Bangladeshi. They were probably Muslim. They were suspected of something.”

“And as far as you could see, they had no families, no baggage of American lives and migrant histories. They had disappeared...”

In the wake of this, another policy only deepened the sense of a data-fueled crisis facing immigrant communities in the US. In 2002, noncitizens from designated groups were forced to appear for questioning by immigration officials, a policy euphemistically described as “special registration.”

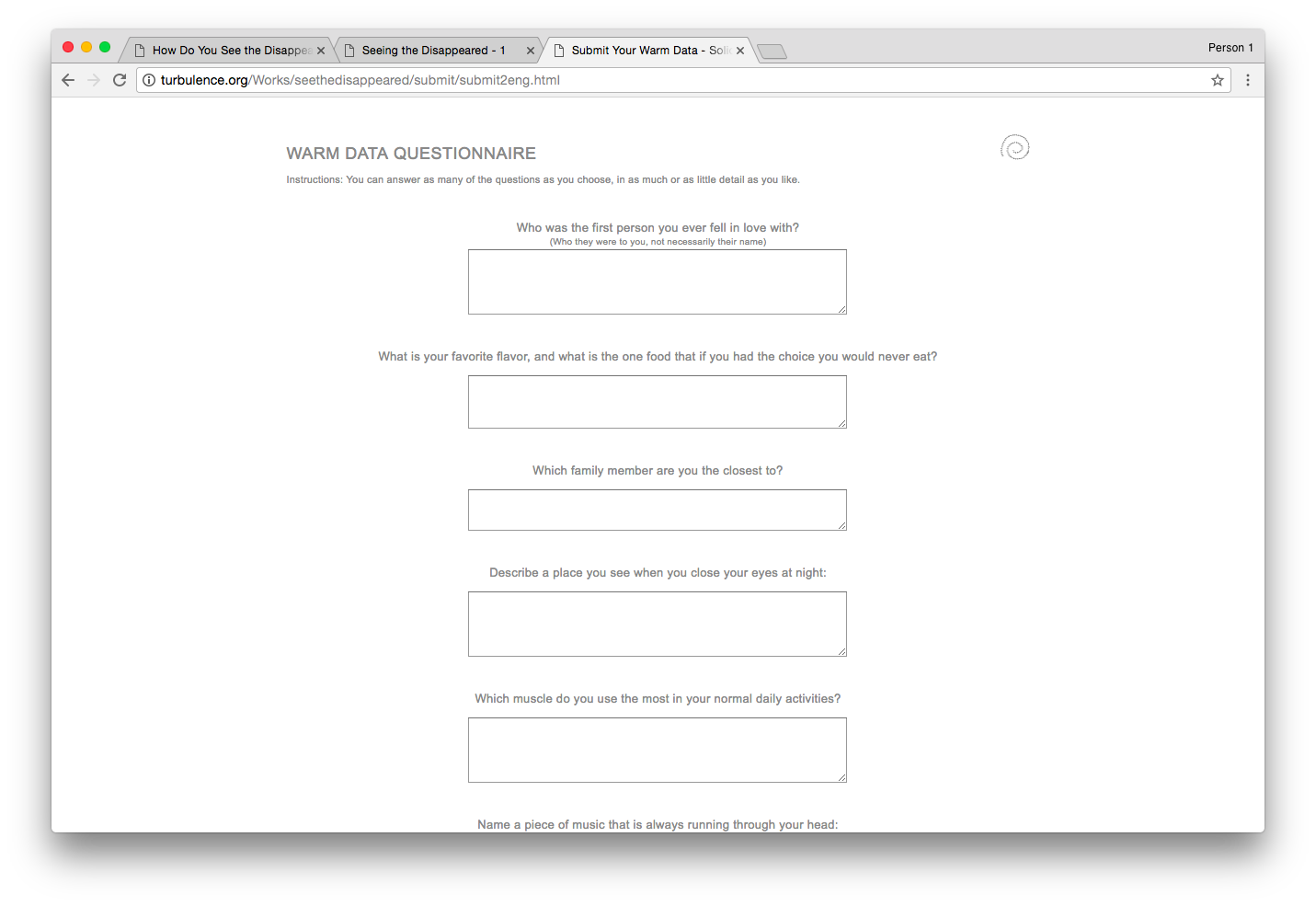

After researching the kinds of questions people were asked as part of the special registration process and spending time with people in detention centers, Ghani began to develop the concept of “warm data.” The opposite of cold facts such as country of origin, warm data would explore the experiences of the disappeared, without revealing the identities or making them vulnerable in any way.

“Could I create a questionnaire, which no two people would ever answer in the same way?”

– Mariam Ghani

This concept was materialized in a website commissioned by Turbulence, which solicited responses to questions such as “What muscle do you use the most in your daily activities?” Responses, which were solicited directly from people in detention centers, and from visitors to exhibitions of the project, were visualized on the website.

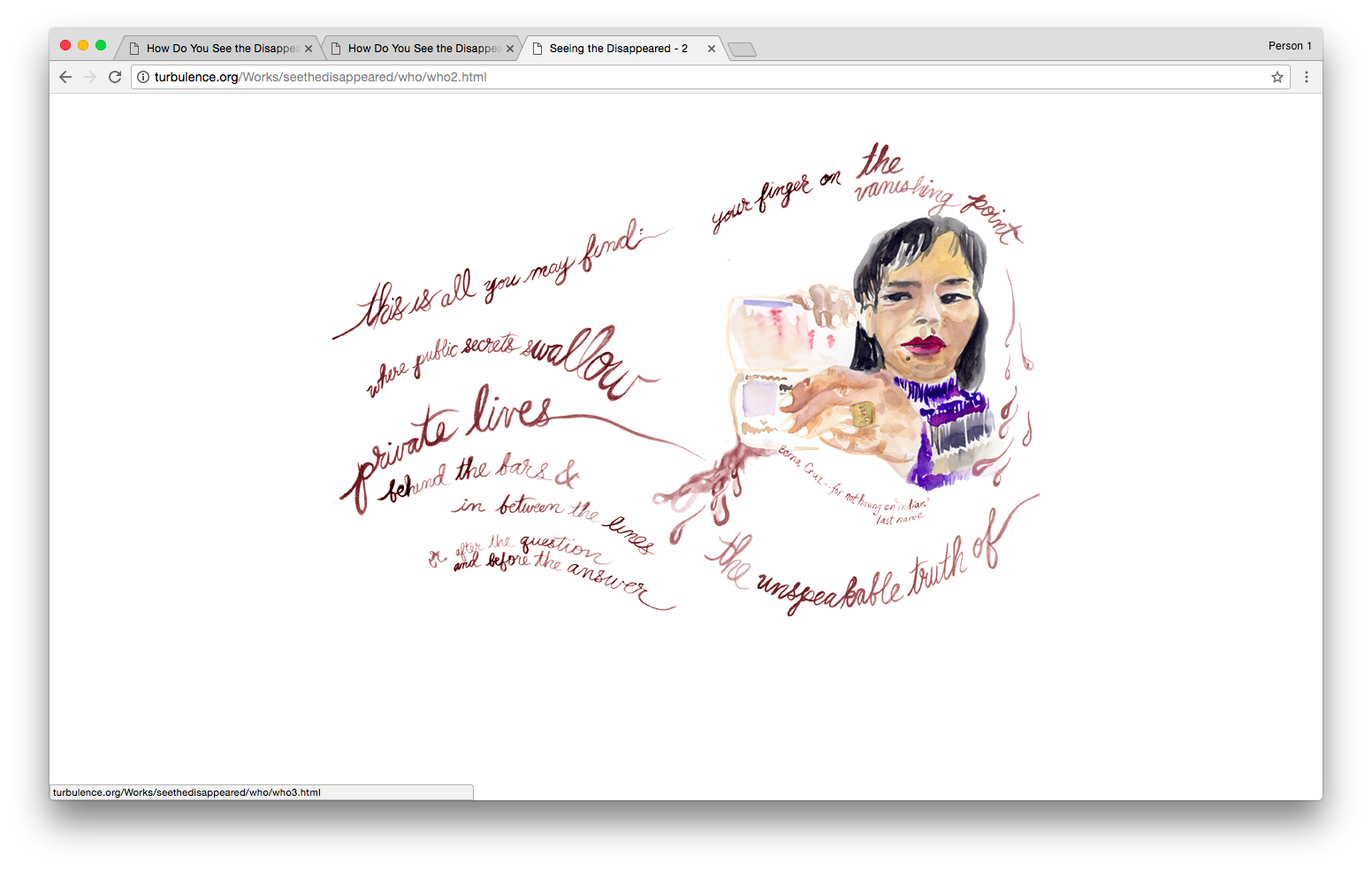

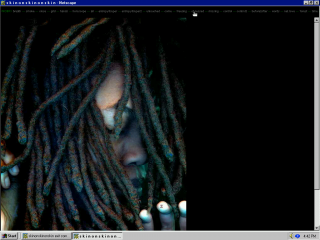

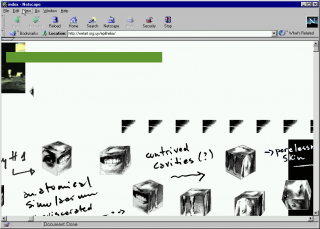

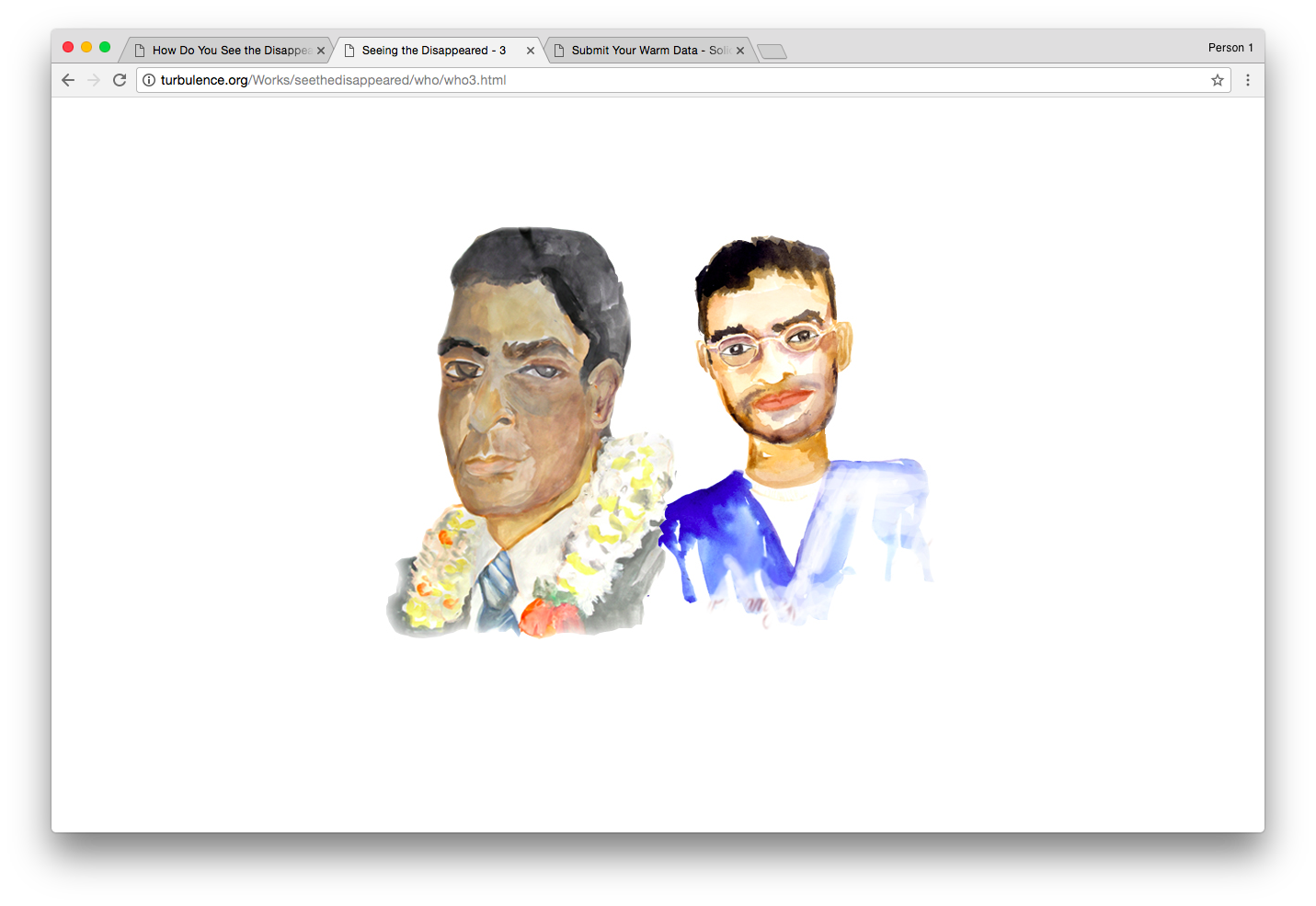

How Do You See the Disappeared: A Warm Database also included a series of watercolors by Ganesh, who chose this way of working as a response to the flyers that covered the city in the days after 9/11.

“Flyers of missing and disappeared people, mainly victims from the September 11 tragedy,” Ganesh notes, “were plastered all over the city's walls, architecture, public transportation.”

For Ganesh, this form of representation of disappearance evoked the parallel disappearance that took place as immigrant communities were targeted for deportation and detention. The portraits in How Do You See the Disappeared: A Warm Database depict people who had disappeared from their communities due to detention or deportation, paired with text fragments from specific stories that were collected for the archive.

As visitors traversed the website, they would encounter calls to action, resources, and stories of efforts underway to aid the disappeared. The project was not merely a representation of a political and social problem–it aimed to spark direct action and bring about change.

The collaboration between Ganesh and Ghani evolved into a larger project titled Index of the Disappeared, which is described today as “an archive of renditions, redactions, detentions, and deportations.”

Introduction to an Index, Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani

Introduction to an Index, Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani

installation view of Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh's Index of the Disappeared

installation view of Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh's Index of the Disappeared

Focusing on what is rendered invisible within the archive, Ganesh and Ghani’s project can be understood as an effort to understand the logic of the archive itself, the power it wields and the violence it enacts. However, it also posits the archive as a site of hope, suggesting that it might be a way to make these processes visible, so that they might be countered.