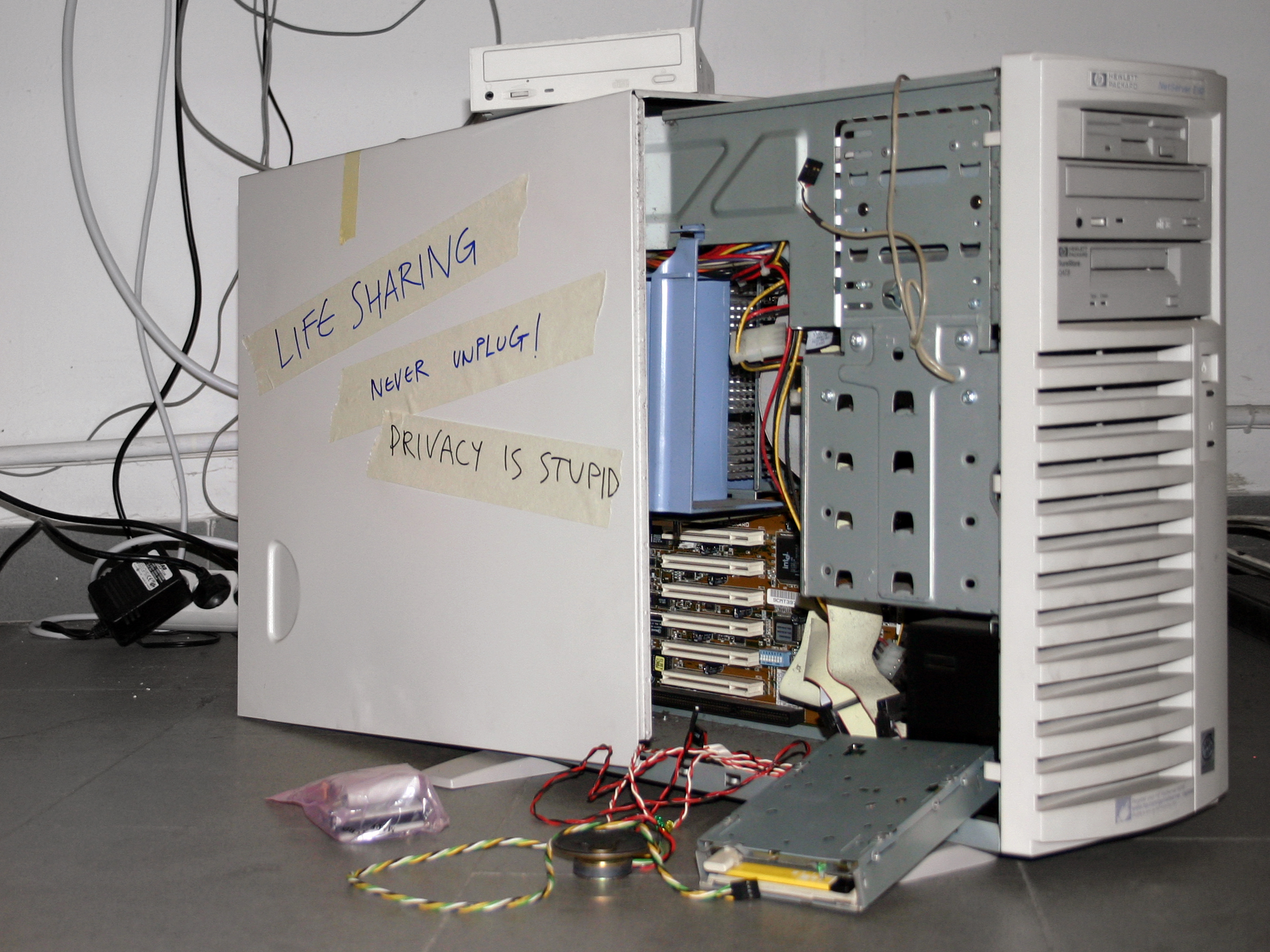

Life Sharing

Eva and Franco Mattes (0100101110101101.ORG)

2000 - 2003

Originally commissioned by the Walker Art Center and curated by Steve Dietz, Life Sharing by Eva and Franco Mattes (0100101110101101.org) was a radical gesture of self-surveillance. For three years, the couple made the contents of their home computer accessible to the public. All of the contents–including files, emails, bank statements, and so on–were available in real time to be read, copied, and downloaded.

Life Sharing was a proto-typical meditation on living online. Made long before social media’s widespread influence, the work pointed towards the blurring of the public and private spheres that characterize our current moment. A performance, a provocation, and a site of exchange, the project was based on the idea that “file sharing=life sharing,” suggesting that life had become inextricably enmeshed in digital culture and the network.

The artists intended to continue Life Sharing in perpetuity, but it became too difficult to maintain, and was taken offline in 2003. Newly restored by Rhizome, Life Sharing can now be experienced as a static archive, an unedited snapshot of the artists’ lives, their artistic community, and the technological milieu of the post-dotcom, pre-social media era.

“A computer, with the passing of time, ends up looking like its owner’s brain.”

–Eva & Franco Mattes

VISIT WORK

Warning: this artwork contains flashing and strobing images.

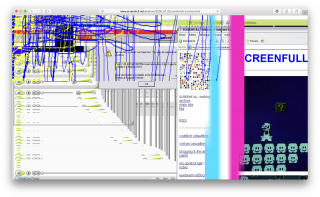

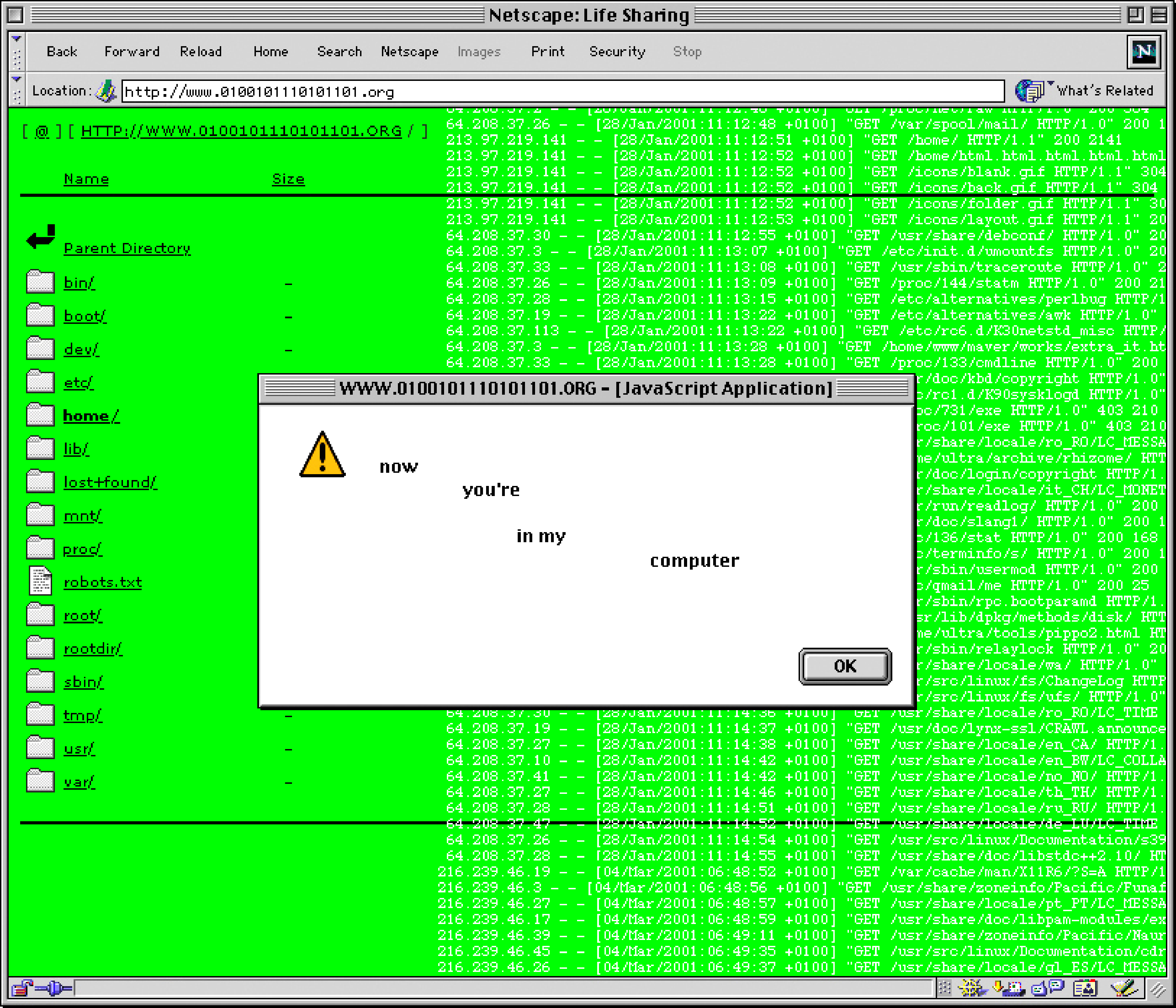

Life Sharing opens with a pop-up window that notifies the user: “Now you are in my computer.” From here, the user lands on a simple green home page, with a file directory lining its left side. Navigating through this directory, the user has access to the Mattes’ entire home computer–system files and personal data alike.

Read an interview with the artists by Paul Soulellis

Legacy screenshot of the Life Sharing home page, from the artists’ archives.

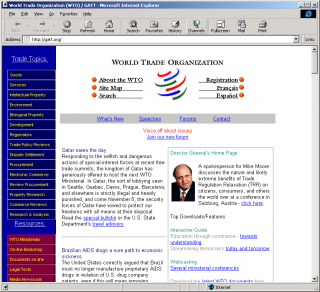

With its title an anagram of “file sharing,” Life Sharing reflected a shifting technological context. Instead of dialing into the internet over phone lines, more users had always-on broadband connections, and they used software tools such as Napster to turn their desktop machines into file servers. This meant that the desktop machine–formerly considered the user’s one private space–now participated in public online exchanges in a new way.

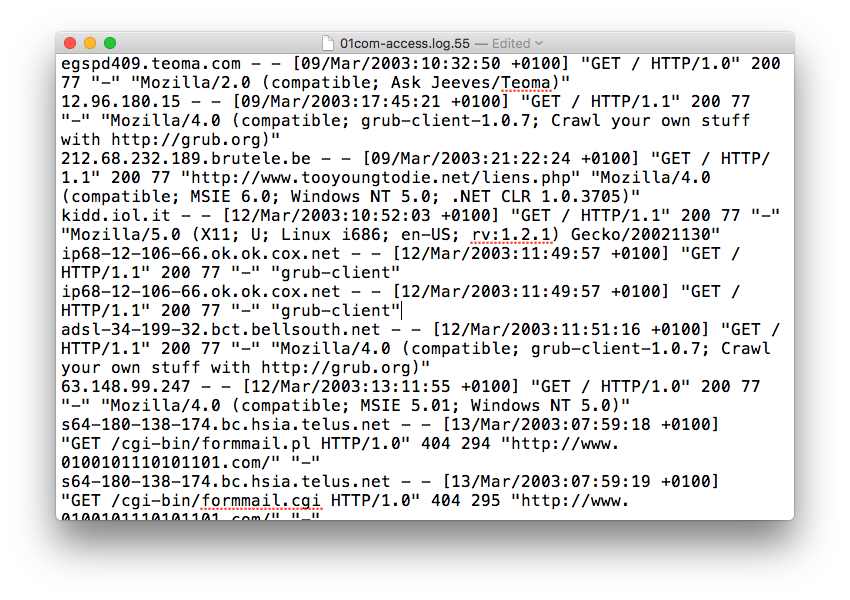

Access log from Life Sharing, showing visit from an Ask Jeeves bot.

“We didn’t have a studio, so the server was physically located in our bedroom — we were literally sleeping with the server noises and the LED lights endlessly blinking a few inches from our bed.” – Eva & Franco Mattes

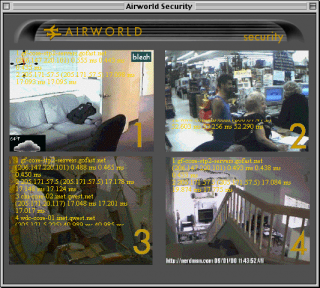

Animated gif made by Eva and Franco Mattes from screenshots of Life Sharing traffic logs.

The project drew a wide range of visitors. According to art historian Megan Driscoll, “the artists report wrangling with opportunistic hackers, receiving warning messages in their log files from concerned citizens, and getting up at all hours to obsessively track the traffic coming in from all over the world.”

“I have had the experience of emailing 01.org about a meeting and having a stranger from Boston reply whether he should come to New York to meet me then also.”

– Steve Dietz

Eva Mattes wearing GPS transmitter at Manifesta in Frankfurt, 2002.

Eva Mattes wearing GPS transmitter at Manifesta in Frankfurt, 2002.

The artists also tapped their own phone, and wore a GPS transmitter. Their most recent location was displayed on a map on the site. In the era before Google maps, this data was requested one jpeg at a time from a family business that monitored the locations of trucks. (The map images–all 18,000 of them–were cached one at a time throughout the course of the project; in the process, some were mislabeled, creating errors in some of this data.)

Animated gif made by Eva and Franco Mattes from screenshots of Life Sharing maps.

Animated gif made by Eva and Franco Mattes from screenshots of Life Sharing maps.

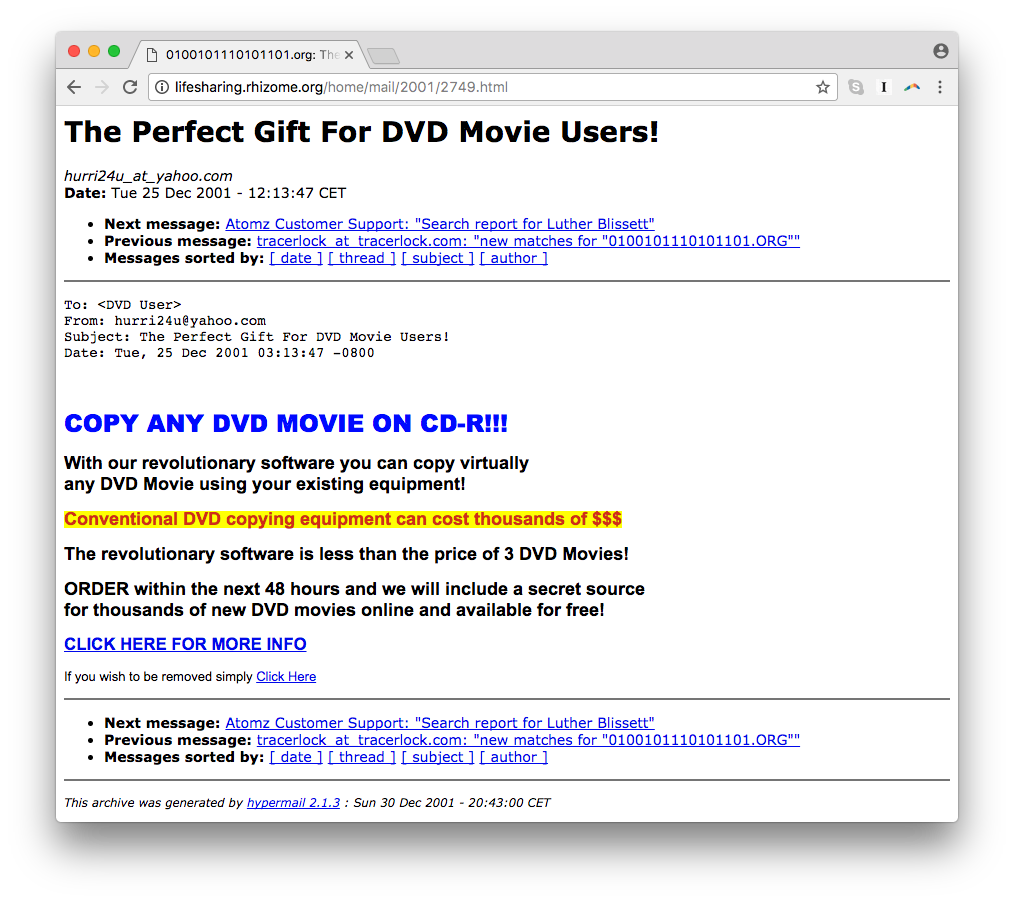

By displaying every last bit of the Mattes’s digital activity, Life Sharing becomes a voyeuristic experiment. On the one hand, the audience is positioned as a constant, unblinking voyeur, and the Mattes’s as exhibitionists. On the other hand, the deluge of data obscures any narrative. Spam and system files overwhelm personal correspondence.

Spam email from Life Sharing archives on lifesharing.rhizome.org.

Spam email from Life Sharing archives on lifesharing.rhizome.org.

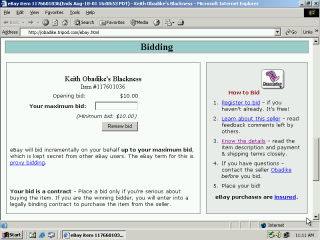

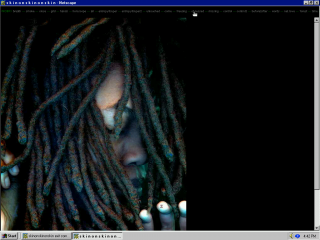

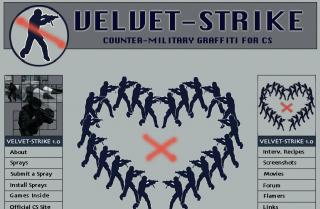

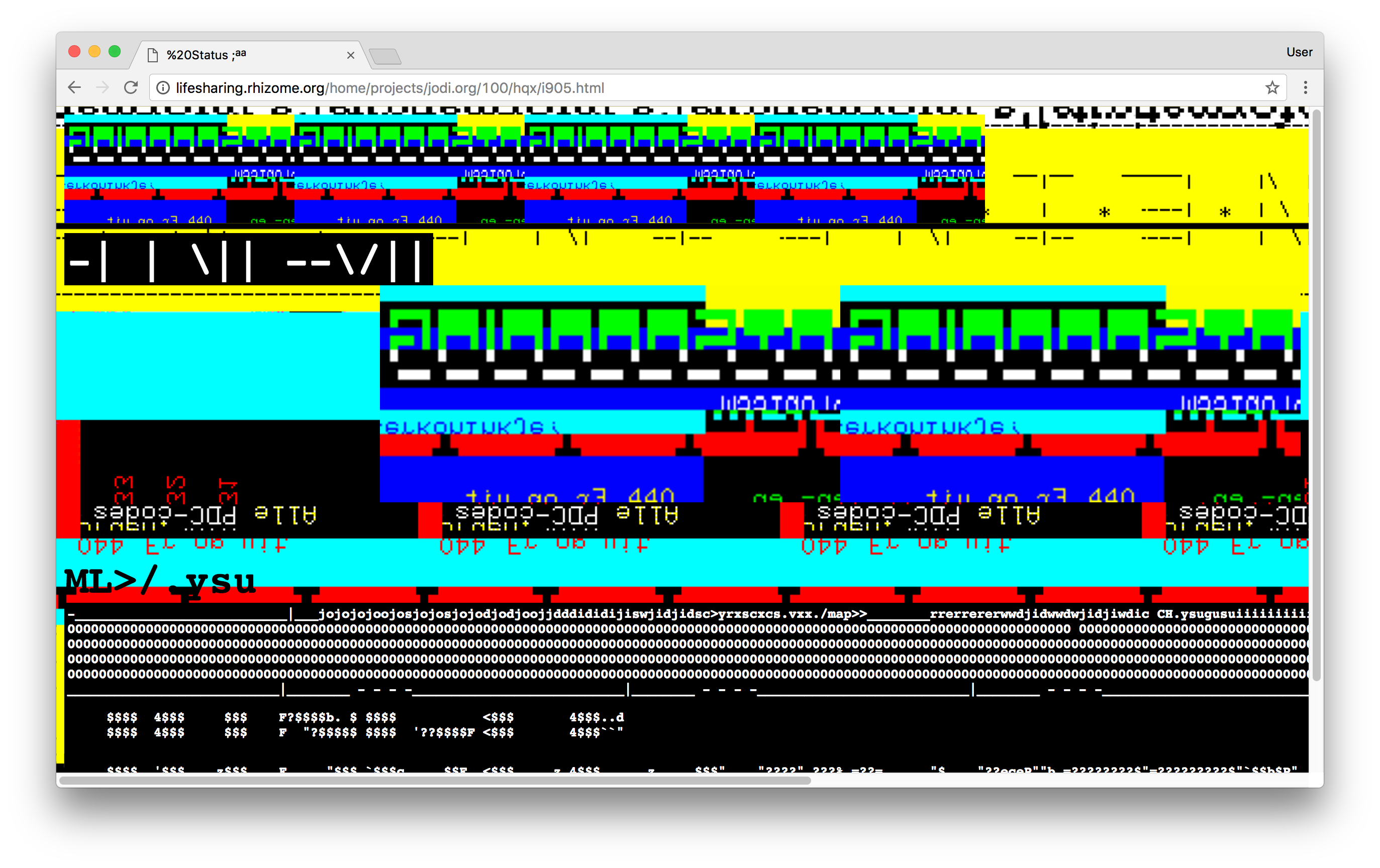

The artists’ relationships with their online community also come across through Life Sharing. Customized page backgrounds include images pilfered from peers such as Heath Bunting and JODI. Copies of entire sites, representing an important slice of digital culture of that time, can be found among its files.

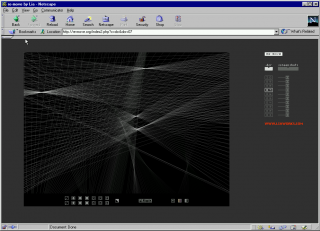

Screenshot of cloned version of JODI, %Transfer | HQX (1998) from the Life Sharing archives.

Screenshot of cloned version of JODI, %Transfer | HQX (1998) from the Life Sharing archives.

“We took the classic hacker slogan ‘information wants to be free,’ and tried to live by it, and discover the consequences.”

– Eva & Franco Mattes

The artists were very aware of mounting concerns about privacy in the face of invasive commercial interests and surveillance, but they also believed that the internet had made traditional notions of privacy obsolete. The personal could no longer be extracted from the computer or the network. In fact, the Mattes’s project is perhaps most intimate because of its least personal content: the presence of spam makes Life Sharing seem truly unedited, and the access to system files exposed the innermost workings of their digital lives to public view and even intrusion.

“Life Sharing is abstract pornography”

–Hito Steyerl

“It had nothing to do with other more titillating experiments happening in the same period, of people living 24-7 in front of webcams etc. In fact, there were very few images and videos in our computer, as smart phones didn’t exist. So the focus of the work was definitely data, more than bodies.”

Once a durational performance, Life Sharing is now (for the first time since 2003) a public archive. The restoration of Life Sharing was managed by Rhizome’s software curator Lyndsey Moulds under the direction of preservation director Dragan Espenschied in close collaboration with Eva and Franco Mattes.